Electronic Healthcare Records , Geo-Specific , Governance & Risk Management

Auditor: Australia's Digital Health Records Need Improvement

Government Auditor Highlights Third-Party Risks

The Australian government's digital health records program manages risk and privacy relatively well, according to a new audit, but there’s room for improvement.

See Also: Panel Discussion | Accelerate HITRUST certification for faster time-to-market and improved ROI

Auditors criticized the program's management of third-party risks as well as emergency access to health records - a kind of skeleton key that overrides a patients’ privacy settings to get access to a record. That kind of access has risen dramatically for unclear reasons.

The 67-page report from the Australian National Audit Office outlines five areas where the Australian Digital Health Agency, which runs the My Health Record program, can improve. The ADHA has agreed with all of the recommendations.

My Health Record, which started in 2012, has had a bumpy ride. The plan was to originally let people opt in to having a record. Slow uptake, however, saw the government change it to an opt-out model, which brought a raft of scrutiny over privacy controls and cybersecurity risks. Some 90 percent of Australian now have a digital health record (see: My Health Record Changes: Too Little, Too Late?).

Adding to the concern is the prevalence of data breaches in Australia’s healthcare sector. Statistics collected by the Office of the Information Commissioner, the country’s data watchdog, show that the sector reported more breaches than any other industry last year.

Third-Party Risk

While the health agency has appropriate systems for managing cybersecurity risk around its core infrastructure, controls “were not appropriate” for broader, shared cybersecurity risks, the auditor’s report says.

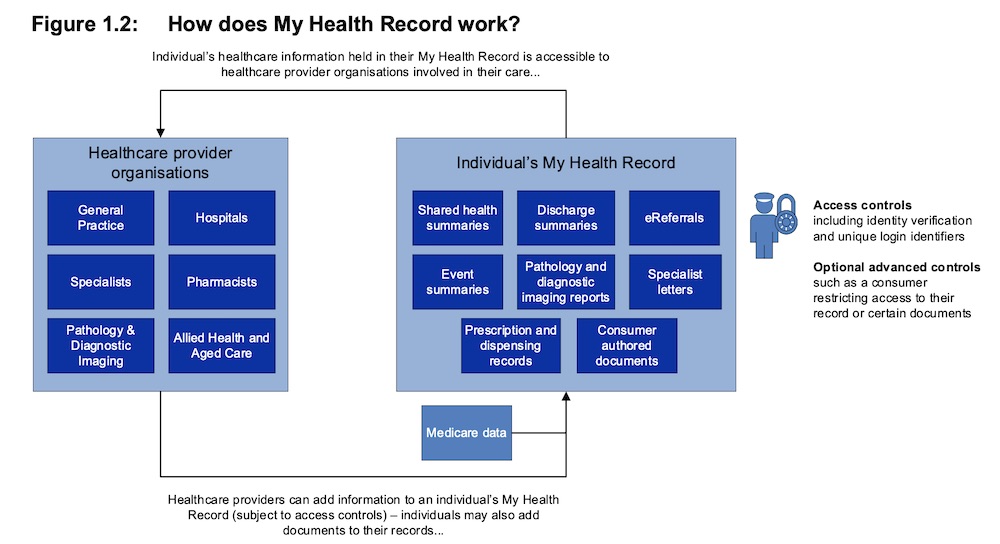

Those shared risks are spread among many entities - some 16,400 health care providers with access to records, citizens accessing records, software vendors that make mobile applications and compatible clinical software and other Australian government agencies.

ADHA doesn’t assess or certify systems to check compliance with the Australian Government Information Security Manual, a series of guidelines developed by the Australian Cyber Security Center.

“The decision to not assess, certify or accredit the ISM compliance of third-party software and systems - as required by the PSPF - limited ADHA’s assurance over the cyber security risks of the My Health Record system,” the report says.

ISM certification would provide a rigorous system to understand risks, but it acknowledges that such a program shouldn’t be so onerous as to discourage participation.

Another key worry is third-party access. Some companies have developed mobile applications where users can access their My Health Records. The access is read-only, but it's another potential point of risk.

For example, HealthEngine – an online medical appointment booking company – enables users to see their health record via its app. The company has been accused of misleading and deceptive conduct by Australia’s Competition and Consumer Commission for selling patient details to insurance brokers without consent (see: Medical Booking Firm Could Face Penalties for Selling Data).

Emergency Access

By their nature, digital health records have to be accessible to clinicians. But if someone arrives at a hospital unconscious, they can’t divulge their access code that unlocks their record.

If this occurs, a “break glass” function has been built in for use in exceptional circumstances. But auditors found that “ADHA did not have sufficient assurance arrangements to satisfy itself that all instances of emergency access did not constitute an interference with privacy.”

The break glass feature was used 80 times in July 2018, before the opt-out model was put in place. In March of this year, it was used 205 times. But the feature was "used as intended" in only 8.2 percent of those instances, auditors found.

ADHA queried healthcare providers as to why emergency access was used, but “in a number of instances, ADHA did not receive a response from specific healthcare provider organizations,” the report says. “In these cases, ADHA could not satisfy itself that the circumstances of the emergency access did not constitute an interference with privacy. In other instances, some of the responses indicated a potential contravention of the [Privacy] Act.

Advanced Controls

Users have at their disposal a comprehensive range of access controls for their record. They can set a PIN, which is required for healthcare provider access provided it’s not an emergency situation.

The advanced controls include a record access code, which is a four to eight-digit character code that can be used to limit which providers can see a patient’s information. There’s also a limited document access code, which can restrict access to specific documents.

Neither control, however, has been used widely yet. The report says that as of June 30, a record access code had been set for 27,215 records, just 0.1 percent of all the records in the system. A limited document access code had been set for just a fraction of that, some 3,862 documents.

Those controls could help balance some of the risks. Three years ago, the ADHA identified nation-states and cybercriminals as the greatest threats to the My Health Record system. “Medium” threats were malicious insiders and hacktivists, the report says.